1930: Tonbridge mourns its R101 victim

At 10 o’clock on a wet Saturday night in October

1930, residents of nearby Shipbourne witnessed the extraordinary sight of the

world’s largest airship – the R101 – passing overhead just below the clouds. A

few minutes later the bright lights of the cabin and the dim outline of the ship

could be seen by people in Paddock Wood as the airship headed towards the coast

at a speed of 50 knots (60 mph).

William King

The R101 was on the first leg of an experimental proving flight heading for

Egypt and then on to India. Fifty four men were on board, including among the

passengers the Secretary of State for air, and among the crew a Tonbridge man,

First-Class Air-Mechanic William Henry King, known as Bill.

Born in a house in

St Stephens Street, King had made a career in airships and was 32 at

the time and unmarried. His parents were living at 8 Dernier Road and were well

known in the town. Five years earlier, King had been one of a skeleton crew on board another

airship, the R33, when it was torn free from its moorings in Norfolk by strong

winds and blown out to sea. The crew managed to bring the damaged ship under

control near the Dutch coast and nursed it back to its base. For this feat King,

with his fellow crew members, was presented with an inscribed watch which became one of

his most treasured possessions.

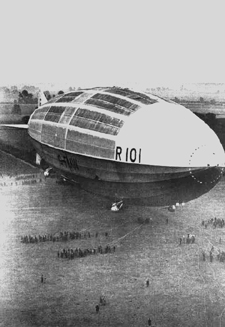

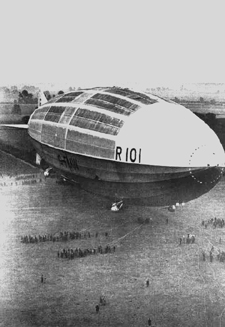

The R101 at its Cardington base (Wikimedia Commons)

The airship on which Air-Mechanic King was serving in 1930 – the R101 – was as

long as a battleship and as high as Nelson’s column. Inside its rigid hull were

huge bags of inflammable hydrogen gas, 500,000 cubic feet (15,000 cubic metres)

in all, providing the lift to keep the ship aloft. Five diesel engines on the

underside turned propellers to drive the craft along. The lavishly-appointed

living quarters were inside the hull, but with windows below so that passengers

could see the landscape passing beneath.

At 1.52 a.m. on Sunday 4th October a receiving station at Croydon picked up a

radio message from the R101 confirming its position over northern France. After

that no more was heard. Soon after 2 a.m. the airship had come down on a hillside

near Beauvais and almost immediately been totally destroyed by fire. Forty-six

of the passengers and crew were burned to death, and of the eight survivors two

would die soon after. It was, in the words of the Illustrated London

News, 'the greatest disaster in the history of aviation'.

Tonbridge hears the news

The wrecked airship at Beauvais (Wikimedia Commons)

News that something had gone terribly wrong with the R101 was brought to

Tonbridge early on the Sunday morning by railwaymen coming off shift, and spread

by word of mouth. ‘Tonbridge and district’, according to the local paper, ‘was

horrified ... to hear of the disaster to the great airship’, with ‘incredulity,

amazement and depression ... written on every face’. Eventually confirmation

came through on the wireless. Special editions of the Sunday newspapers were

produced and large crowds assembled near the newsagents in the High Street to

await their arrival. Supplies were sold out in minutes and more had to be ordered.

Special prayers were offered at Sunday services and the flag on the Castle

lowered to half-mast.

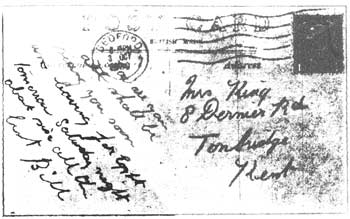

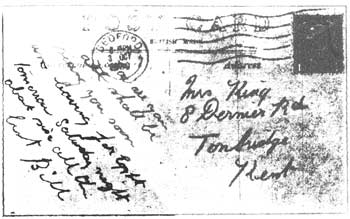

Postcard sent by King to his parents the night before the R101 set off: 'How are you all

- shall

be seeing you soon - am leaving for Egypt tomorrow Saturday night about six - all

the best Bill'

At 10 o’clock on the Sunday morning Mr and Mrs King received a telegram from

the Air Ministry at their home in Dernier Road saying that their son was

reported missing. This was confirmed in a later telegram from an Air Ministry

official: ‘I am commanded by the Air Council to express to you their great

regret to learn that your son, Mr W. H. King, was among those who lost their

lives in the disaster to the R101 over Beauvais this morning, and to express to

you their most sincere sympathy with you in your bereavement.’

Soon after noon on the following Wednesday the funeral train bearing the bodies

of those who had died passed through Tonbridge station, where ‘reverence and

homage was paid’. From Victoria Station the coffin of Bill King, with 47 others,

was taken to Westminster Hall to lie in state while tens of thousands of

mourners filed past. On the Friday one of King’s brothers and two of his sisters

were present at a memorial service in St Paul’s Cathedral at which King George V

was represented by the Prince of Wales, and on the Saturday

the whole family attended the funeral at Cardington in Bedfordshire where

the airship was based.

The 48 victims of the R101 disaster are buried in the cemetery of St Mary’s

church, Cardington, where a prominent

memorial commemorates them. Pensions and gratuities were awarded to the

widows and children of those killed in the accident, though in King's case,

since he was unmarried, the family only received a single payment of £125

(equivalent to about £5000 today).

Court of Enquiry

The report of the Court of Enquiry issued in April 1931 recorded the likely

cause of the accident as loss of gas at the front end of the airship probably

resulting from a tear in its outer skin caused by buffeting by wind. It was

clear, too, that pressure for the flight to coincide with the ‘Imperial

Conference’ being held in London meant the ship had set off before an adequate

programme of testing had been completed. When the even larger Hindenburg

was destroyed by fire in New Jersey seven years later it was clear there was no future

for hydrogen-filled airships.

The captain of the R101, Flight-Lieutenant H. C. Irwin, who was among the

dead, had many years' airship experience and was said to be someone who

would never take unnecessary risks. He was on record as saying that 'there

is a feeling still among the public that airships are not safe. That is

quite wrong. As a matter of fact they are safer than sea ships ...'.

Further information about the R101 and its crew and pasengers can be found on www.airshipsonline.com

Much of the

information on this page comes from a report in the

Tonbridge Free Press of

10th October 1930, available on microfilm in Tonbridge Reference Library.

▲Top