1849 and 1854: Cholera comes to Tonbridge

In the nineteenth century Tonbridge could be an unhealthy place in which to

live. A number of diseases, such as typhoid, were endemic and there were

periodic epidemics of smallpox and cholera. The latter was particularly feared

because of its sudden appearance, unpleasant symptoms and high death rate. John

Snow did not publish his research showing that cholera could be transmitted

through drinking water until 1855 and before then there had been a number of

theories about its cause. However, some observers had noticed that it seemed to

thrive in unhygienic and over-crowed living conditions.

"cottages of a wretched description ..."

"bloated carcases of dogs were floating ..."

There were two particularly serious outbreaks of cholera in Tonbridge in 1849

and 1854, when thirty-nine deaths were recorded, and although this mortality was

relatively low compared to other areas it was sufficient to persuade a number of

local ratepayers that something needed to be done. An inquiry under the

provisions of the 1848 Public Health Act was, therefore, conducted by Alfred

Dickens into the sanitary condition of the town. His subsequent report gives us

a 'snapshot' of Tonbridge in 1854 and provides an insight into the living

conditions of its poorer inhabitants.

An alley (now called Owlett's Alley) led off the High Street to one of the worst slum areas,

abandoned after cholera struck in 1849. McDonald's now stands on some of the site.

Dickens was a conscientious Inspector. He walked round the town, making notes

in his memorandum book, and he also heard evidence from a number of residents. A

rather bleak picture emerged of a picturesque town with some dirty and squalid

areas. The inquiry highlighted problems resulting from the housing boom in the

1840s and 1850s when three farms virtually disappeared under the new streets of

south Tonbridge and in-filling behind the High Street resulted in substandard

houses being built in new courts and alleys. The condition of much of this new

housing was criticised by Dickens. Witness after witness described poor and unsanitary living conditions which

undoubtedly contributed to the Tonbridge death rate being higher than the

national average for similar locations.

There was also a clear difference

between Tonbridge north and south of the river with the death rate in the latter

being higher. A local doctor, John Gorham, was in no doubt about the reason for

the high death rate. He noted that Tonbridge south of the Big Bridge was

unhealthier than the northern part of the town because of 'its low level with

reference to the river Medway, accumulations of filth, dirty and offensive

privies and pig-sties, very imperfect drainage, and equally imperfect water

supply'.

"filthy, dirty and offensive privies and pigsties ..."

"pitiable child ... ill of fever ..."

Other witnesses also described the inadequate, or even non-existent

sanitation and poor housing south of the river. No wonder that Dickens concluded

that this area 'is scarcely a fit site at any time for the erection of

houses…Cottages of a wretched description are crowded, notwithstanding, on each

other in this district, and … are built with a disregard of decency and

convenience, and are charged in themselves with fresh causes of disease'.

Industrial pollution was also a problem and the report details complaints about

a fell yard, whose effluent drained into the Little Bridge stream, and a tallow

chandler’s melting establishment.

A water company had been founded in 1851 but at the time of the inquiry only

176 houses and 2 schools were connected. As there were 1,121 houses and cottages

in Tonbridge it is clear that the majority of the population drew their water

from one of the public pumps or from a private pump or well.

"cholera completely decimated the inhabitants ..."

"large, full and open cesspit ... vast amount of filth ..."

Although the report paints an unpleasant picture of the sanitation, drainage

and water supply in Tonbridge, principally in the part of the town south of the

Big Bridge,

Dickens believed that a number of things could be done to help. And conditions

did improve although it took time. Many Tonbridge ratepayers were not

immediately convinced that radical change was needed and the town had to wait

until 1870 until the newly formed Local Board began the work of improving

drainage and sanitation, widening the High Street and demolishing many of the

substandard properties criticised by Dickens.

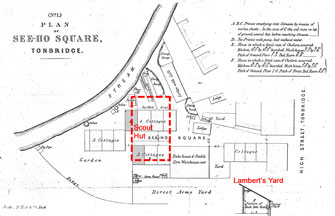

See-Ho Square, off the High Street, was one of the town's slums.

Dwellings where people died of cholera are shaded in this plan from the Dickens

Report. The present-day Scout Hut and Lambert's Yard are shown in red.

(Map reproduced with the permission of Kent Libraries & Archives – Tonbridge

Library)

A number of plans form part of the Dickens report, two of which

illustrate how the area behind the High Street and below the Little Bridge used

to look. The first, reproduced here, is of Lambert's Yard and its continuation Seeho Square, where

the first fatal cases of cholera were reported in 1854. The second shows

Snelling's Row, now known as Owlett's Alley. Both plans show the density of housing

in these areas, the lack of privies and the close proximity to cottages of

nuisances such as a slaughter house, stables and an open dung heap. Nowadays Lambert's Yard and Owlett's Alley look very different from the

residential areas that they used to be. Their substandard housing has gone and

they are largely given over to commercial use. There is a McDonald's restaurant

on the corner of Owlett's Alley and the High Street and Tonbridge Country Market is

held on Friday mornings in the Scout Hut in Lambert’s Yard. The present day

visitor will find no trace of the former cottages and their inhabitants.

>Brief quotations from the Dickens Report appear on this page. If you are interested in finding out more about the state of Tonbridge in the

early 1850s the report is worth a read. A copy is held in the reference

section of Tonbridge Library.

>An article on cholera and typhoid fever in Kent is on the

Kent Archaeology website.

▲Top