In 2010 Tonbridge Historical Society received a copy of part of a diary kept by a German soldier who had spent three years in the Prisoner-of-War (POW) camp at Somerhill. His name was Vinzenz Fetzer and he was captured in France in October 1944. He did not return to Germany until early in 1948.

Vinzenz Fetzer (photo from Jochen Fetzer)

Vinzenz's grandson, Jochen Fetzer, now has the diary and was put in touch with the Society when on holiday in England in 2009. He provided a copy of 32 pages of the diary and all of this has been expertly translated by one of our members, Joyce Buswell, although a few words and phrases could not be worked out due to difficulties in reading the handwriting and use of army slang. Parts of the Diary appear to be the author's edited transcript of the notes he made at the time. It is a remarkable, and sometimes moving, testament.

In World War 2 each POW camp was allocated an official number in a prescribed numerical sequence, starting with Camp 1(Grizedale Hall in the Lake District) through to Camp 1026 (Raynes Park, Wimbledon) but the numbers can be confusing since not all numbers were used yet the same camp number could be used for camps in different locations. There were 456 identified POW sites in Great Britain, 376 of them in England and the Channel Islands. The one at Somerhill was Camp 40.

Vinzenz's diary starts with his transfer from France to England after capture by American soldiers. He was sent first to Camp 195 (Merevale Hall Camp) in Atherstone, Warwickshire, arriving there on 25th October 1944. This was designated as a base camp and the diary gives details – partly in verse – of the camp routine.

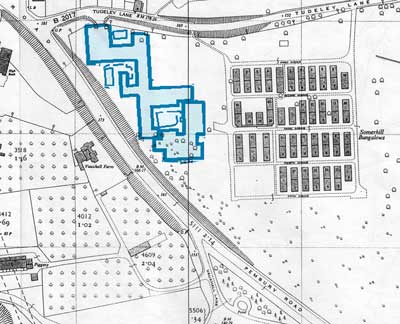

The former POW camp is labelled 'Somerhill bungalows' on the right of this postwar map. The present buildings of Weald of Kent Grammar School have been added in blue.

On 10th April 1945, Vinzenz was transferred to the Somerhill camp which was designated as a 'working camp' and consisted of wooden huts on land that is now in the grounds the Weald of Kent Grammar School. He was to stay there for the remainder of his time as a POW (although he spent 18 months of that time at what he calls 'Horns Lodge hostel' – probably at Horns Lodge Farm, off Shipbourne Road).

He was 39 when he arrived in Tonbridge and had been a gardener in Stuttgart before the war. His delight in the Kent countryside is shown clearly and he appreciated the scenery as he was sent out to farms as part of a work party. On page 23 he describes working at 'Churchill's place' (Chartwell) and what a lovely location it was, also referring to Churchill coming back to the house from America. He expresses his anxieties and worries about his family in Germany and the importance of letters from them and the pressures and tensions of being a POW. He also, when at Horns Lodge in October 1946, looks back at the difficulties of life in Germany under the Nazis and how he eventually had to join the Party or risk losing his job.

When World War II ended Britain had around 350,000 captured soldiers in POW camps, mostly German or Italian, and the programme to repatriate all these men was given the name Operation Seagull. At its height 15,000 POWs were on the way home but the process was not complete until 1948. Vinzenz describes how the barracks became emptier as more and more of the prisoners left until finally it was his turn. His last words are 'God grant that all comes to a good end and a happy beginning'.

After his release Vinzenz returned to his parents' farm in Denkingen in south-west Germany and eventually set up his own nursery garden. He died in 1978. His grandson believes that if Vinzenz had not had family back in Germany he might well have settled in Britain for good.

Page 1

Now the way led through a meadow with trees surrounded by wire. Soon we could go no further and so tents and equipment were brought out. We erected the tents in the middle of the mud and then slept well. As tent poles we had to use the branches of fruit trees which reproachfully stretched their lopped-off limbs into the dark sky. For many of us our clothing was now torn but as a precautionary measure I had put on an old duffle coat and luckily later kept my hands warm. It was already night and we still had no water and terrible thirst. Finally we were able to draw water from a pool about 100 metres away. The way led through mud, ditches and embankments and the buckets were half spilled out by the time we got back. We then filled them up again straightaway. The accompanying American was very helpful and often lit our way with his torch. On the next morning rain again – rain. We only crawled out of our tents to get food. Many had spent the night out in the open sitting up. Today is the 21st of the 10th 44, Mother’s birthday it suddenly struck me. What will they be doing? Will they still be alive? Later, only in 1946 did I find out that they were completely bombed out in July 44. On the 22nd 10th 44 pm came the order "Prepare to march off". That came as a relief. It didn’t matter where to as long as it was out of this mud, we all said. We were formed up in rows and after we had stood for some hours, the order came "March". It was quite an odd feeling to march on firm ground towards the sea, past large American tents, among negro soldiers and the odd French man.

Page 2

We marched for 6 kilometres, then 3 kilometres along the beach. We were very impressed by the harbour installations which were erected here at the start of the invasion and the vast number of ships which we saw. The fortifications on the shore were minimal. It was low tide and we could see footprints going towards a transport ship whose loading bay doors were down and stores were being taken on board. About 300-400 metres out from the shore was the sea and the ships were firmly resting on the sand. Now we too went up and came to a long high space about 70 by 5. To the front of the ship and beneath the engine room the steel plates were warm so where possible, everyone sought a place there. Sacks were hung up with water such as we’d previously seen. The Americans had organised everything for ease of transport. Their soldiers, the negroes among them, have made a good impression on us all. On strict military orders, they don’t shoot at anyone as was usual with us. On the ship there was the usual trading with the Americans of souvenirs of all kinds. They sold us cigarettes, 20 for 300 French francs, chocolate packs for 500 francs, watches for 200-800 cigarettes. They didn’t get their pay in francs so liked to get hold of them. On the 23rd 10th at 1.00 in the morning we departed and were disembarked on 24th 10th 44. We were on the ship for 37 hours and saw nothing of the outside world. I wasn’t seasick but many were . In Southampton we reached English soil which we were not to leave again so quickly. Up till now we had no opportunity to write. What will my family think? We worried about them most of all.

Page 3

Not far from the harbour, we were quickly behind barbed wire again but without tents with walkways and sections, so a transit camp we said. As guards, we had only English soldiers. Soon a passenger train drove up to near the wire but first class, so it couldn't possibly be meant for us prisoners. But when steps were positioned up to the carriages, we had to believe it. In single file we marched and were again counted. From experience each of us had taken sections of crates or cartons as a base to lie on in the tents. All of this had to be left behind and strengthened our hope that we were going to a more permanent camp. Almost everyone had a seat and we were soon travelling through the autumnal English landscape, which had a very soothing effect on my soul, after all the travails of the past weeks. Towards evening we arrived at Hampton near London. A stricter mood prevailed here. Orders given in German – Quick, Quick-etc. Once again, barbed wire – a large yard – many prisoners. Orders through tannoys. Separate units were formed and we had to line up accordingly and alphabetically. After a time there was warm food, then to our positions again. There followed a rigorous inspection. First a photograph, then each of us received envelopes then out into the yard again. Everything edible was now disposed of. Then after some waiting around, back to a large room. "Strip off!". Everything off and put on the table. One item after another tossed onto a pile, clothing into a sack, valuables into a pouch Naked, shoes in our hands, onto the scales, see the doctor, into the shower room, disinfectant sprayed into the shoes. Showering, with sufficient soap, was ,after the previous lack of water, a relief. Each of us then got his clothes sack back, then out to a tent, get out your clothes and quickly dress, guards on watch nearby.

Page 4

"Hurry up, throw things on". Half dressed, our remaining clothes in our arms, the bag with our bits and pieces we had to give in, but where to put the stuff, all our pockets were stuffed full, but we still didn't want to throw away the few possessions left to us. Everything in a towel or a flannel and then another march in single file to the rear of the railway, surrender our cards then on into the yard to be given some bread then line up again. Meanwhile, I finished getting dressed, got my belongings together, and any piece of material that I found in the yard for use as a cover. Then back to the station, into the train, first class with tables. Most of us soon fell asleep, we were on the way for 2 hours. I got all my stuff together and pored over each item like a child- pencil, rubber, wash bag, laundry bag, knife, gas mask, letters etc. which I read. Watch, letter pouch, photos I also had, also a sewing kit. Photograph, search, train, dismissal, all in a few hours. When, on 25-10-44, we arrived, at daybreak, at Camp 195 in Atherstone, I still had with me a faded laundry bag which accompanied me everywhere.

I was in Camp 195 until 10-3-45. I wrote fewer notes there, as there was a dearth of paper and pencils. The camp was big and in an old park. A walk around the barbed wire perimeter fence took half an hour. I didn't do any work there and completely gave up smoking. Our rations were very good, sufficient and varied. In the first four weeks things were a bit short until everything was up and running. There my stomach recovered and gave no more trouble until 1946.

Page 5

Many courses took place which I attended. I also sang in the choir and was never bored. RC and Protestant services were held but with only 15% attendance.

March-April 1945: Camp 194 Penkridge

On the 10.3.45 about 1,000 men, able to work, went from Camp 195 to Camp 194 at Penkridge. There was grumbling, and with the sergeants, it was a bit like being in a madhouse. I can scarcely believe that people of sound mind can forget themselves beyond all reason and reality. Life in our barracks was bearable as we had a very reasonable, clear thinking barracks leader, with whom one could speak as one thought.

My day's routine is written as follows:

P.O.W. gets through the sunny afternoon

In leisurely fashion step by step.

For him every day is a holiday

For whom there is no work.

Every day's routine is a picture of rest.

Against good practice, many are unshaven and tiresome.

But a good razorblade does not last.

The P.O.W.'s uniform is awful.

Green and red with patches, round and square.

Grey, blue and black.

Freshly laundered to your taste.

Each day starts with trumpet call.

On rising, one hears many a heavy sigh.

Grunting and yawning, whinnying as in a stable.

Page 6

Then we go to breakfast two by two.

Creamed rice or bread and jam.

Even this pleasure passes

And so begins our daily trouble and trial.

Washing, bedmaking and other chores.

Then summoned by hooter to the general rollcall.

The company perform firewatch drill

In the big square, five by five.

There stand ‘The Old Man’ and ‘The Squirt’

And observe all around the grass and flowers.

‘Enemy coming’ is the call.

‘Aid detachments’ order the camp leaders.

The sick are counted first

Then the normal rollcall begins again.

The numbers are correct.

Now begins our free morning.

One counts off the number of walks round.

Another occupies himself with improvements.

With chess and card games so the hours pass.

Then again a mealtime is announced.

With much ‘love’ our helping of stew is prepared.

Page 7

Then follows a quiet time

One hears snores intermittently.

Each one rests, full of food.

Now and then goes to pee.

Afternoon exercise

If not taking part in a class.

Otherwise we don't enjoy our supper.

Also it is good for rheumatism.

The cold damp weather is especially felt in one's joints.

Lots of lying around makes one's body soft and one's spirit depressed.

One's life here is like Heaven.

The path there is steep and not without obstacles.

Eight o’clock and again a rollcall of poor and rich.

And at half nine we must lie on our beds.

Here we must lie until 7 am.

It's not a real rest.

But one talks of home by the starlight

And sooner or later sleep and weariness overcomes us.

It's life behind bars.

One feels it hard.

We've never had it so ‘fine’ all of our life.

Yet in the silence each one craves activity.

Camp 40

We've been given a last chance

To do something for mind and body.

You needn't lie around on your belly

Now each one should work.

Page 8

The portions got smaller and smaller

Our bellies shrank with stomach pains.

Many a one had blisters on their hands

Our backs hurt and we walked stooped.

Yet soon these ‘mercies ‘came to an end

And mind and body came under more strain.

On the 10th of April 1945 I arrived, with other comrades, at work camp 40 in southern England near Tonbridge. This area is called the Garden of England because of its mild climate and well-tended orchards, hop fields and oast houses. For several days now I have been travelling with my work party by omnibus to a farm about 35 kilometres away and every time it is a pleasure for me to drive through such thriving activity. In the towns you can see in front of most of the houses a neat and pretty front garden filled with flowers. The villas on the edge of town have correspondingly larger gardens, also flower-bedecked. The lovely English lawn is prominent. You also find tastefully arranged rock gardens with flowering plants. At the moment in bloom are shrub carnations, tulips, narcissi, trumpet lilies, forget-me-nots, lilac and hedgerows of Japanese cherry, primulas and the many rockery flowers. The orchards in blossom are also a splendid sight – mainly apples, also damson plums, some cherries and pears. Cider is produced from the apples which are not eaten fresh. This is sweet and sometimes fermented. From the plums a fruity jam is made. I have also seen a hazelnut plantation.

Page 9

Growing everywhere are deciduous trees – oak, birch, beech, linden, willow, alder, larch and ash. The cattle pastures are bordered by whitethorn hedge or other thickets. You could see game – rabbits, wild deer, pheasants and wild hares. The bird world is varied and rich and is a many-voiced concert at dawn – robin, thrush, blackbird and finch. The dwellings are mostly two storeys high (ground floor plus one storey). One often sees a two-family house divided in the middle. Almost everywhere bay windows are built on for both storeys. The building material is almost exclusively brick, simply mortared. Older houses are built from rough stone. Also on the first storey, roof tiles are overlapped vertically on the wall. One often finds a little annexe or extension. The roofs are made of tiles or thatch. Country and farmhouses may be of a timber construction. In a farmhouse, the living quarters are always individual and apart from the stables. Stables and sheds are very primitive. The fencing boundaries between the individual houses consist of natural hedges – privet, whitethorn, beech and more rarely juniper. The windows of the older houses and country houses have lots of lead surrounding the window panes.

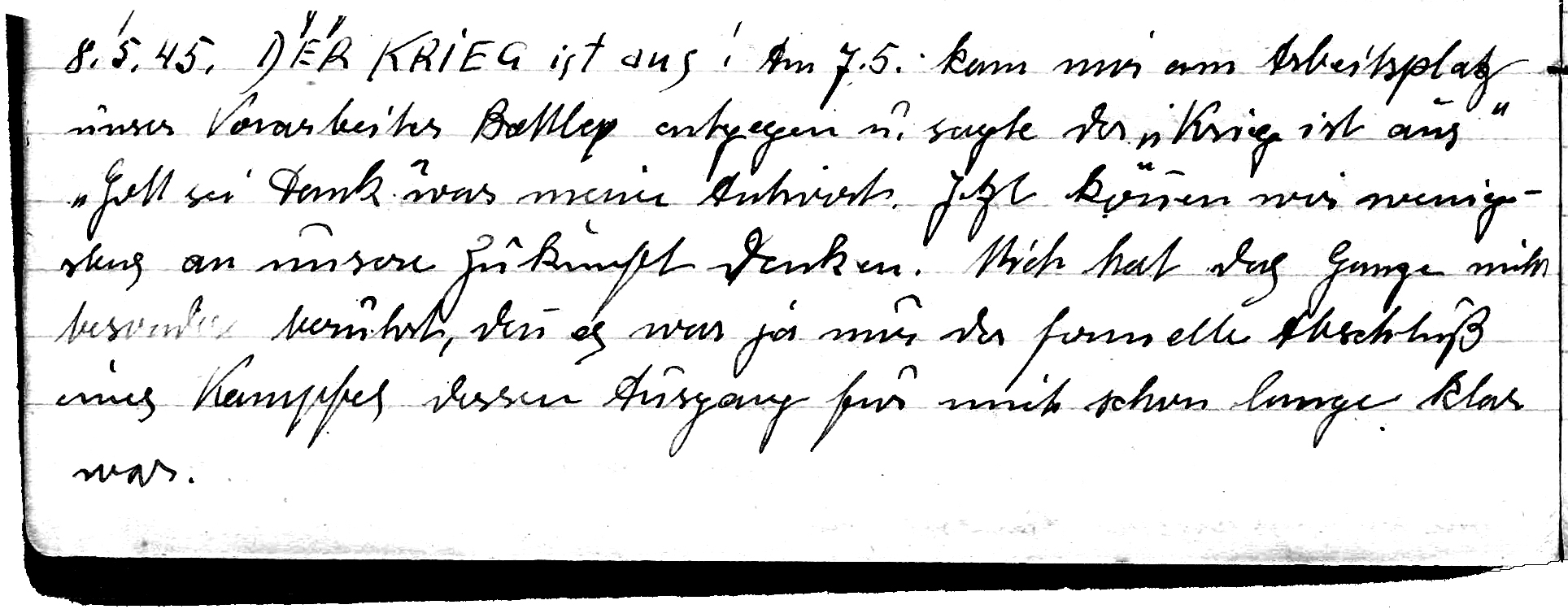

8.5.4

THE WAR IS OVER! On the 7th of the 5th in my workplace, our

foreman/supervisor came towards me and said "the war is over". "Thank God"

was my answer. Now we can at least think about our future. The whole thing

did not particularly touch me since it was only a formal conclusion of a

struggle whose outcome had long been clear to me.

DER KRIEG ist aus! The war is over. Part of the diary entry for 8th May 1945. It would be

another two and a half years before Vinzenz Fetzer could go home.

Page 10

For a long time I couldn’t understand the senselessness of all this. I was definitely aware of it when I came to be in prison on 11.9.44 and that it was to do with the system, that it was the intention of our leadership, when things could not be saved, that everything should be ruined, even the people and its wealth. From this crime the national leadership cannot be absolved. The people were knowingly lied to and deceived for years. I was very fearful that means would be used that might decimate the rest of the population. That the National Socialist leadership shrinks from nothing, they’ve shown often enough in this war. Ruthlessly and cruelly, measures were taken against everyone who thought other than prescribed. When there are today in prison, people who wanted to stand up for our leaders, then it’s incomprehensible to me. As an outer sign of the end of hostilities, the signs on our backs and sides disappeared.

No greetings from my family for a long time. Since 23.8.44 I knew nothing of them. But I hope this month to get post from them. If my loved ones are still alive then I can bear things that I haven’t been able to get over. Everything can be replaced except life. Now things will be hard for our old parents if two of their sons don’t come home. On 21-22.4.45 my home town of Stuttgart was taken by the French. The population will be relieved that they can sleep again after so long a time. Hopefully we will soon go home.

Page 11

English farming has been greatly mechanised since the beginning of the war. You find few horses but tractors and cars everywhere. Most farmers are good stockmen but bad husbandmen. English farming has much to make up if it is to be on a par with ours. The many large concerns have the advantage since here machines can be profitably used.

The people are very angry and hostile towards us which can only be attributed to propaganda. Children are for the most part friendly, if at first fearful. I can see straight away whether they are affected by the old people's views or whether they regard me as a human being.

13.5.45

On the 8th-9th May was V.E. Day. In line with the English character, this

day passed off peacefully and calmly. For the English, victory was secure.

We saw many little flags on the houses – American, English and also Russian

but nowhere a big flag like with us. We have great hopes that now we can

soon go home.

23.5.45

Today I had dental treatment from an English dentist. Last Sunday was

Whitsun. The weather was misty and cool and on Monday thundery. Both days

were days of celebration. At this time we felt the pull towards home more.

We didn't do things much differently – an outing with wife and child,

friends visiting, relaxation. At least the war is over now and at home they

can sleep peacefully again. If I only had some "sign of life" from my loved

ones. For 10 months now I don't know what can have happened to them in all

this time. At Whitsun we had good food, I wonder whether they will have

enough at home.

Page 12

28.7.45

The war countries' executive committee (WAEC) is an organisation to

encourage improvement in agricultural yields. It provides for the deployment

of additional workers, the deployment and hiring out of machines. The

committee also manages whole concerns/enterprises in war situations.

Unfortunately, most of the working men and foremen are not land workers. We

are in the area around Westerham, Oxted, Godestone, Lingfield, Grinstead,

Cowden and Edenbridge.

15.8.45

Today is a Victory Day now that Japan has been defeated . Many of the house

are not decorated with flags. England has also made great sacrifices.

1.9.45

Recently we drove past Tillingdown, a small town that at first glance,

reminded me of Triberg in the Black Forest.

2.9.45

Once again a Sunday is over. It's always the same, the same not knowing and

anxiety. No news of home, no prospect of release. Tomorrow we go to work, in

the evening we come back, wash, have our evening meal, then each one amuses

himself in his own way – cards, chess, reading, model making, learning,

mending. Now and then we also talk politics and think of our personal

situations as a result of increasing uncertainty.

Page 13

Recently for the first time, we saw two films – The Other Self and The Flaxfield. Also there was the camp choir and camp show as a change. But all of that can’t prevent other thoughts from turning to home on Saturdays and Sundays. Are they still alive? Do they have a roof over their heads? We lead a wretched existence, having just what is necessary – the smokers not even that. At the moment we are threshing out in the open with four machines.

23.9.45

On the 18th I celebrated my birthday, the 2nd in captivity. I think there’ll

soon be a 3rd. In the morning, on wakening, my thoughts were with the loved

ones at home. Whether they celebrate birthdays at home?

29.9.45

Today we wrote a "Missing Persons" card. Since then I’ve been very restless.

What will happen? Some change in the camp. Some pictures were very good when

one thinks by what means they were created. The camp choir and band gave us

a good evening. In a talk, we got to hear news from home. It wasn’t to give

us courage, we are a defeated slave people.

In the last three and a half weeks we have had lovely autumn weather.

21.10.45

Today was mother’s birthday and my betrothal day. For 8 years we were on

life’s journey together. Then for 4 years separated with only brief leaves

of absence. Heard nothing in a year. How long will this miserable existence

last?

Page 14

After my last leave in March 1944, I felt something like cold dread. Either we won’t see each other again or not for a very long time. I don’t know what will happen. Tonight I dreamt of Sofie. Yesterday I felt so sad and low, my thoughts always of home. So I can’t believe they are not still alive. When my whole thinking and planning and feeling is that it is possible with the help of my lucky clover leaf.

27.10.45

Since the 23rd, the effects of a bad storm and as a result heavy

downpours, which have caused great damage on the coast. Some men have

already received answers to their cards, so far so good.

4.11.45

All Saints and All Souls, solemn days at home. With not much to do, we

have sharp disagreements.

The village squares in English places are laid out in a triangle bordered

with streets around. For shopping bags they generally use wicker baskets

here.

11.11.45

A disturbing week with ugly scenes lies behind me. One can’t believe that

among grown men such stupidity occurs, and in a prison too.

Page 15

6.12.45

With new courage I begin this Page. Today I received an answer to my card –

all well. I couldn’t expect more. My belief, my hope – not disappointed. No

mention of the house. Now all anxiety is at an end. My clover leaf has

brought me luck.

9.12.45

Today I wrote the answer. Wishing happiness to the senders at home, last

postal letter from there 23.7. All my hopes confirmed. To live on,

purposeful, confident, full of hope. Working on the land April 45. Health

good, food satisfactory, homesickness great.

16.12.45

Second card. Since 12.12 we worked on the Kent Committee.

23.12.45

Third card.

29.12.45

Christmas is over. Thank God, many a one will say. It’s precisely this

family festival which weighs heaviest on the mood of the prisoners. It was

worst for those who still have no news from home and for those from the

Russian-controlled zone who up to now are not allowed to write.

Kitchen and bakery have done their best to make Christmas as pleasant as

possible for us. There were German-style pastries, Christmas Stollen,

cigarettes and good simple food.

Page 16

A short simple Christmas celebration with Christmas tree. At each table a candle and in the festively- decorated dining hall, everyone could understand the importance and meaning of this festival. The music emphasised the warmth and depth of the Holy Eve. On both feast days there was music – the camp choir in a Christmas concert in the barracks. On the water tower of the kitchen an electrically- lit Christmas tree shines out into the countryside since Christmas, greeting our loved ones at home, as it were. In the church, alternate Catholic and Protestant services were held in the festively-decorated space with our home-made Christmas crib. The church barracks could not accommodate all who wanted to attend the Catholic Midnight Mass. And so the feast days passed, dignified and peaceful, even if not all of the men could be of good spirits. All barracks were decorated with Christmas trees, mistletoe and holly as is usual in England.

30.12.45

4th card, Christmas festivities

6.1.46

5th card, wrote fully.

New Year’s Eve was celebrated by some in the camp. In general it was

peaceful, if in contrast to the Holy Night when a sombre, almost melancholy

mood prevailed. A merry, lively and hopeful mood arose. A German knows how

to celebrate the feast days. Through it all, a gentle hope that next New

Year’s we’re back home.

Page 17

Many are aware that those at home will not expect anything, but are still resolved to keep going for their relatives and homeland.

13.1.46

6th card

20.1.46

7th card

27.1.46

8th card

In the command the mood is good again. The enthusiasm for work decreases the

less prospect there is of going home. Post comes from the Russian Zone.

1.2.46

First letter from Sofie dated 18.1.46 via Frankfurt. This letter gave me

more details.’Completely burned out’ was one sentence. Finally ‘think

confidently on your clover leaf and look after your health’.

3.2.46

1st letter to Denkingen. 9th card to Switzerland.

6.2.46

In the past weeks there was a change in the monotony. On the 6.2 I ended up

in the glasshouse for 7 days on account of unmilitary behaviour. On the 6th

day they let me go. These 6 days let me think a great deal and have given me

greater recognition of things. On the 13.2 I got the first card since my

request card of 19.1.46 and on 15.2 I got an answer to my card of 1st.2.46

to Switzerland.

10.2.46

10th card to Denkingen

17.2.46

Card to Strasbourg. 2nd letter to Denkingen.

24.2.46

12th card to Krenzlingen.

3.3.46

13th card to Alsace. 3rd letter to Denkingen.

10.3.46

14th card to Denkingen. . Snowfalls, severe trials, snow shovelling.

Page 18

17.3.46

4th letter to Denkingen. 15th card to Denkingen.

On the 15.3 four cards came from Stuttgart, from Sofie. They did not give me

much clarity but afforded the opportunity to put a host of questions.

18.3.46

Today a letter came via Switzerland from Krenzlingen. In contrast to the

cards, it gave me coherent news. There was also a picture of mother in it.

She still looks good. The picture pleased me so much.

A Look Back at Military Unit 27. 1.1.1946

Old and young are here together

From Germany and the Netherlands.

A new situation from among our people

And from many another land.

Old Austria and Czechoslovakia

Are great again, strong and free.

Swabia, Bavaria and so on

Are all again ‘Forerunners’.

Grey, blond and black,

Beards, moustaches, bald.

Beards and goatees must soon

Give way to a ‘higher’ power.

Tall, short, thin and fat

But the latter had no luck.

Often there was trouble and strife

But it never went too far.

There was in many a head

If not much – then lots of sense.

Page 19

But finally we pulled together

And many a one was ‘re-christened’.

The ‘return home’ receded

So ‘Oschima’ didn’t want to live any longer.

Yet he will be remembered for all time

In ‘Oschima tea’ for nervous problems.

Even the professional butcher at times went off track

But soon that seemed too stupid a thing.

His cans and tins and pots

Confuse him and others too.

Colour, varnish, BovrilOXO

Onions, biscuits and white bread.

Our Peter collects it all

And what he doesn’t need now, he keeps for later.

The ‘merry tailor’ took each one by the arm

And made for where it was dry and warm.

The ‘policeman’ wanted to put his head through the wall,

But despite that he stayed in England.

Viennese humour coped very well,

In the shape of the vocalist in our camp choir.

As an Austrian he got to hear things

But that couldn’t disturb him.

The ‘Leipziger’ or filthy swine, played it dumb at first

But soon he acted like a jumping jack.

Not forgotten is ‘grandad’

Who, despite his age, provides us every day

With coffee and tea and good humour.

Page 20

Every day he conjures up a’fire’,

Richard, ‘just take a look’, our crazy Fritz.

Leo ‘the brush’ who sings in the morning,

Calm and peaceful is ‘father troubles’.

The ‘Pharisee’ lay in bed one day

And soon after that he was in the sickbay

Many a one took to fooling and teasing.

Many felt affected by that.

In 4 weeks of time there were also ‘flirtations’

Hopefully they will never regret it.

Love is charming with the opposite sex

Also quite natural and quite right.

But against nature and unhealthy

With the same sex and brings ruin.

One or the other doesn’t feel good alone

And doesn’t know how to change that.

Hanspeter and Hans came closest to a solution,

Many a one acts like a savage dog,

Not nice are the words from their mouths

But there’s always some truth in them

And they fulfil their purpose and meaning.

The unit leader is often envied for his extra merits,

Each one grins at the extra work.

Fill out lists and tables are put

Before the quartermaster for hours on end,

Running off to meetings and the office,

Buying cigarettes and other stuff in the canteen.

Be told what to do by the foreman.

Page 21

Be complained at by the Committee

About this and that, well that's fun.

Many also think it was 'cause of them alone

That he became unit leader.

One can only laugh at that

For 25 men belong to the unit.

They thought to derive some privileges

For times to come.

There was talk of misused trust,

Yet who speaks thus, is not to be trusted either.

At this time also, thick and heavy came

Thunderclouds from the camp.

Gone was the domestic peace.

There was scolding, hounding and vexation.

A plot was hatched,

The leader should go.

Ill-considered and forced,

Quickly then an announcement was written.

By persuasion they wanted to force

The Devil's work to succeed.

The whole unit had to take

A pot shot at the leader.

But the shot went off behind

And then they were in the soup.

For whoever digs a pit for another,

Often ends up deep in the mire himself.

When all was discussed and the quarrel past

There was nothing left but petty jealousy.

Page 22

But whoever seeks zealously what another does,

Has thought too little about himself.

Jealousy and false ambition is not good at all.

It makes one's heart and nerves go to pot.

A man should always behave like a man

Or he will be a scandalmonger and should be ashamed.

Not all are wise themselves when bile poisons their blood.

Meanwhile the thickest clouds have gone

And one can again praise the mood.

Many have received post

But for many, it is all the same.

Many a one has more than he dared hope for.

Many a one has been tormented in vain for years on end.

Yet each one is happy and satisfied

If their loved ones are alive and well.

The future is no longer gloomy and grey

When parents and wife wait at home.

It's hard for those from the Russian zone.

The Homeland sun does not shine for them.

They wait in hope for the day

Which will bring them certainty.

Christmas is now past.

It brought all kinds of surprises.

Each one tend his body.

Also beseech God's blessing.

Mind and heart rejoice in music.

Ask from God for Homeland happiness.

All in all we can say

We have managed this year quite well.

Page 23

A part of winter is past

And basically it is all the same to us.

Our New Year's wish is quite small,

"By Year's end we want to be at home."

If one of us privately feels down,

Then don't let it show on the outside.

For "whom" it affects, that which here rhymes,

Will take on board that is meant for him.

24.3.46

16th card to Denkingen. On the 20th a card from Wolfgang.

On the 23rd a card from Sofie and Fr. Mayer Kallental. The card from

Wolfgang pleased me so,

it testifies to hard work and simple understanding.

3O.3.46

17th card to

Stuttgart, Frau Mayer. 5th letter to Denkingen.

Today we had to finish our work at Churchill's place. Yesterday he came to his country house with his wife. He came back from America a few days before. It's a lovely place in a sunny situation. The house is on a southeast facing slope. In the valley are two lakes. The whole area must encompass c.12 – 15 hectares and is surrounded on three sides by woodland and open to the south. In the park one finds many types of trees and rhododendrons. 7.4.46 18th card to Stuttgart, Hubert.

10.4.46

A card from Sofie from 11.2.46. Up to now 9 cards and 2 letters received.

Now working on a hop farm. Cherries and plums in blossom. 14.4.46 6th letter

to Denkingen. 19th card to Gasman.

Warm weather – fruit ripening, blossoms. Strong pains in my legs, rest

prescribed.

Page 24

31.12.46 New Year's Eve.

If it weren't in the calendar, we wouldn't notice it. New Year is not a

feast day and Silvester a day like any other. The weather is spring like and

warm. The past year brought us many a disappointment and some surprises. The

biggest disappointment was the slow rate of repatriation, which pans out at

15,000 per month over 25 months. In the last few days we also learnt that

Group 15 can reckon on going home by the end of June. A bad outlook for

Group 21. At Christmas we were surprised to have our first outing. It was a

strange feeling when, on Christmas afternoon, after 27 months behind barbed

wire, I walked along the road as a partly free man. Then I thought of Franz

when we, at Easter 1942, went walking in Heilbronn, while Sofie was in the

Maternity Hospital in Stuttgart. I felt sad. The people barely acknowledged

us though many greeted us.

On the second day of the holiday I was in Tonbridge and among other things,

I took a look at two cemeteries, one old, one new.

The Christmas days passed calmly and in a generally good mood. I decorated the dining hall and arranged the serving dishes, which helped me best of all get over the ever-present mood of melancholy. On Christmas Eve, at food, Rapp spoke some words and reminded us of our loved ones at home. The band played some Christmas carols to which we sang along. After the general celebration, we celebrated in our hut and our spokesman, Karl Weber, thanked each for their cooperation. Miggi then told tales about his P.O.W. Life, which were in fact not quite respectable but we could laugh and the time passed.

Page 25

A Look Back – Horn Lodge

October 1946

After all that is behind me, I feel that it is not wrong to cast a political glance back. One thing I must straight first – "I've never bothered much about politics." I always tried to see life ideally and to find goodness in everything. Brought up as a good Catholic at home, it was quite obvious that I would choose the Centre Party (Centrum) or later, because of my job, the Farmers' Alliance (Bauernbund). I never gave much thought to my choices. I'd no time for S.A. and the like, for playing at being a soldier must lead to war again one day and that horrified me when I thought of what misery war would cause. We were also brought up anti- war by our father. He'd been a soldier in W.W.1 and he'd threatened us with blows if it should occur to us to even designate a Mark for the war loan at school. With each Mark, war and misery were only extended, he always said. I was often asked to cooperate somewhere, I always declined, not always to my advantage.

In April 1939 when I went to the gardening department in Stuttgart, I soon heard that several people were dismissed since they were in no organisation, or had spoken against the N.S. Policy. Now, I was able to keep quiet because things did not interest me that much anyway. But soon my attention was brought to the fact that, in the 'city', each one must join in (mitmachen) somewhere. I didn't react to that. In winter 1939 it was indicated to me that the Party was now open and a favourable opportunity for me to join. Our Head of Department was S.S. Sturmfuhrer or something like that. I was fairly much the only one not to be in an organisation somewhere. I considered backwards and forwards.

Page 26

It had already become hard for me after the requirement to come into town from the country where I was then in a better position, for in the country, in my job, it wasn't so easy as a married man to get a good position. Already I'd given up a good job because I wouldn't join in. If I now lost this job, it wouldn't be easy to find something good again. I was only a blue-collar worker but a job on town was securer for a married man. S.A. S.S. or such like I did not want, because there was much duty involved and so with a heavy heart I registered with the Party. If I thought I would have to do no duty here, then I was much mistaken. Now here, now there, there was something to do and if I excused myself that I had no time, well that was ok a few times but then I was told it was my duty (Pflicht).

I preferred to devote my free time to my family, I seldom went out, so I found burdensome the work imposed on me.

In February 1942 I had to report for duty in the army and my connection to the Party stopped then. But here I got to know the true face of National Socialism. I thought the army was an honest, correct institution, as it was always portrayed, but I learnt something different. I soon became convinced that there was nothing more shameful than being a soldier in Hitler's army. I could never be a good soldier. This was also the case with promotion, only after one and three quarter years was I promoted the first time, to NCO.

1943 I was transferred to a communications unit and there I was lucky to get to know politically aware men – teachers, professors, pastors who really showed me what National Socialism was.

Page 27

At this time my 2nd brother died, one already in 1941. I began to hate the system, that hounded men to death like dogs, that brought distress and misery to mankind and for what actually? They told us we had to defend the Homeland, why then did they start this war? With these kinds of questions and insight, you had to be very careful. Many of my comrades went to the Eastern Front, never to return because they had expressed too free an opinion. I was long ashamed of my Party membership and it would have been a logical step to withdraw. But what that would have meant for me and my family anyone who lived in Germany then knew, it was terrible. But none of my comrades ever found out that I was in the Party; they would really roll their eyes today if they knew that. I always found those who were of the same mind as me and with whom one could speak openly. In the last months before my capture in September 1944 I counted the then company commander among these. Once, when we had spoken for a long time about these things and the situation, he expressed himself thus: "Gentlemen, if someone has overheard us and reported us, we would all be up against a wall tomorrow."He had thoroughly denazified the company HQ already at that time. My friend Schick was in mind for one position, but as a fanatical Nazi was shunted over to something else. So the commander asked me if I thought he was suited to it. I said certainly but he has only the one failing, he is not 100% Nazi. He looked at me and smiled and my friend took up the original position.

Page 28

In the radio corps I had some young men for further training. Instead of wireless lessons, I often talked with them about what was taught them in the Hitler Youth. It pained me to hear with what illusions these young men had been inspired for the cause and to hear their attitude to life. They were 18.19 years old but they told me – why do we need to learn so much, we’ll still be shot one day and we’ve enough knowledge for that. It wasn’t easy to rouse in them a personal ambition and desire to learn. Some later thanked me because through my work of explanation, they found courage in life again and were transferred to battalion or regimental wireless troops where things were easier and not so dangerous.

Also, later in captivity, I often tried to give young men a firm basis on which to stand and move into the future. Otherwise I seldom took part in political talk but adopted my earlier stance, for all was surely lost. From the start of the invasion I knew the war was lost for sure and it was terribly hard for me when I thought about the senselessness and the awfulness of this hopeless struggle. How long should this mad slaughter go on, was there not more than enough blood shed already, enough misery and horror visited upon women and children. I didn’t know anything about my family either, only much later did I learn that they’d been bombed but were still alive.

Page 29

22.1.48

Now it’s done. Today the last work day. It’s an odd feeling when you do work

for the last time which you’ve done for 16 months. I didn’t consider myself

a P.O.W. in my work place as far as the work was concerned. Best of all was

the freedom in my work. I wasn't compelled, I did bigger jobs quite

independently. My knowledge of horticulture and fruit growing came in very

useful and my boss was soon convinced of the quality of my work. He wasn't

sparing with appreciation when it came to special jobs. The farewell

discharge today corresponded to the nature of my boss. He is

a clever but down to earth businessman. He pressed a pound note in one hand,

pressed my other hand, and thanked me for all I had done in the sixteen

months and wished me luck for the future. Without expecting an answer from

me, he turned and went off. All without warmth or cordiality but it didn't

affect the value of the pound note. His wife gave me a bottle of beer and

when I sought her out in the evening, she gave me 5 shillings (a crown) and

asked me to write to her sometimes from home. I thanked her for all the good

she had done for me in this time and told her that the good times I had

spent here as a P.O.W. I would not forget. She, without making much of it

had given me many a tasty snack and many a friendly word. She was pleased by

my thanks.

So time goes, and everything comes to an end if one can endure it. The important thing is to be true to oneself, then in the end all will be well again. Now only days separate from my loved ones, but they seem longer than the months before. But this too ends and a new life of freedom begins.

Page 30

29.1.48

It's even emptier in the barracks, one after another goes off, never to be

seen again. Today the folk went to the Russian Zone, a transport to the

hotel in Mereworth, and we, the returnees to the French and U.S. Zones are

alone with a part of the work force and some of the staff who work on

building sites. All is a bit confused like in the time of the first

occupation by German P.O.W.'s in April 1945.

Nearly 3 years spent here, with 18 months 'interval' in Horns Lodge hostel and I am now among the last to leave the camp, to make room for homeless people from Germany. It's been spoken of in fact that the town of Tonbridge is against it, they don't want strangers any more in their town but want the camp grounds to revert to their former purposes, sport, above all golf and other general activities.

For years we’ve lived together here, worked, shared our worries, always our thoughts on our homeland and our sights ahead to the point in time when we’ll go home, when our army time is over and we can again lead a civilian life, free. For most, this time has come and for the rest it’s within reach. They must make the whole move again with all their belongings, blankets and palliasse of which they’ve long had enough.

Each one then goes his own way, each in a different direction and a very few of them will, in later life, see each other again. But each will sometimes think back on these years of separateness, of being marked out, all the petty harassments and all the good and loyal comrades and also on those who didn’t want to adapt, who were always troublesome.

Page 31

One needs much good will to adapt to life en masse, to be satisfied with a narrow space on one’s straw sack which was bench, table, resting place, writing table all in one. The two tables for 50 men were always occupied by card players. Here you can see how little one needs to cope. No cupboard, no feather bed, no chair, nothing cosy. Just a kitbag and when things got better a small case or bag for which there was scarcely room to stow it.

Many will also look back fondly to many an enjoyable hour which the acting group, the band or camp choir gave us. Also the well-tended grounds gave refreshment to eye and mind. Many an English person and family too has left a lasting memory for many which they’ll think back on gladly. Many a tie of friendship was forged which will last beyond captivity.

Already for days now the rubbish containers along the camp streets are filled to overflowing with tins, old items of clothing, shoes, cartons etc which are superfluous. Our kitchen equipment comprised large and small tins eg teacups, porridge pot, teacan to boil tea in at your workplace, drinks beakers, wash bowl – all durable, cheap and unbreakable.

It seemed strange when one was invited the first time to an English family – to a table laid with plates and all the usual cutlery. Reminders of times long ago surfaced.

Page 32

But in the pleasant cosy setting, one quickly settled and then the longing for home, family and homeland was all the stronger. Now we shall soon have this back again, see this all again. God grant that all comes to a good end and a happy beginning.

We are grateful to Jochen Fetzer of Bingen in Baden-Württemberg for making copies of the diary pages available to us and permitting us to publish them in translation on this website, and to Joyce Buswell for deciphering and translating the pages.

Diary text and photographs: © Jochen Fetzer